Planning

Accreditation period for Units 1 and 2 from 2024; Units 3 and 4 from 2025

Introduction

The VCE Politics Study Design Units 1 and 2 from 2024; Units 3 and 4 from 2025 Support materials provide teaching and learning advice for Units 1 to 4 and assessment advice for school-based assessment in Units 3 and 4.

The program developed and delivered to students must be in accordance with the VCE Politics Study Design Units 1 and 2 from 2024; Units 3 and 4 from 2025.

Characteristics of the study

Thinking politically

These characteristics provide a framework for the study of VCE Politics and should be explicitly taught. They are detailed in the VCE Politics Study Design 2024 on pages 12–14 and describe what it means to think politically, analyse political issues and evaluate political significance. The Characteristics of the study should underpin the teaching of the key knowledge and key skills. The characteristics align directly with the key skills in each area of study and are embedded in the outcomes and the key knowledge.

The following eight characteristics represent the procedural concepts and methods that provide the tools for students to analyse and evaluate political issues.

1. Undertaking political inquiry

1. Undertaking political inquiry

Investigating contemporary issues: The study of contemporary political events and issues is central to VCE Politics as a discipline and provides a natural foundation for political inquiry. ‘Contemporary’ is defined as ongoing or having occurred within the last ten years. It is the investigation of examples and case studies that promotes student curiosity, deepens their understanding of political phenomena, and enables them to analyse and evaluate political issues on the basis of evidence.

An issue in VCE Politics can refer to any kind of local, national, regional and / or global problem, challenge, crisis or situation that gives rise to differing perspectives on its resolution. Thinking politically about issues such as challenges to democracy, pre-selection battles, social and economic inequality, territorial disputes or global issues and crises (for example, climate change and human rights disputes) requires students to inquire into the nature, causes and consequences, power dynamics, interests, perspectives, proposed solutions and political significance of these issues, as well as their impact on political stability and / or change. By thinking politically in this way, students will gain a balanced understanding of the complex challenges facing communities nationally, regionally and globally.

The VCE Politics Study Design provides a number of ways in which political inquiry can occur. For example, teachers may choose a case study for investigation in any of the Units 1–4 as a vehicle for introducing students to key political concepts and political knowledge. In Unit 2, teachers could encourage students to create and convert their own inquiry questions into the options provided by using the typical stages of either inquiry learning or problem-based learning (see ‘Stages of the inquiry process’ below). In Units 3 and 4, a class could undertake a guided inquiry across the whole of each unit as a means of addressing key knowledge and key skills (see the detailed example of a Group Research task in the Teaching and Learning activities for Unit 4 Outcome 2). Assessment of individual student achievement could be via either Stage 4 or 5 or 6, or all three combined, of the inquiry process. Alternatively, students could create their own case studies of issues or analyse a number of existing case studies to construct their own inquiry.

Teachers are reminded that a political inquiry is one of the mandated assessment tasks to be undertaken at some point throughout Units 3 and 4.

The following ‘Stages of the inquiry process’ offers a general guide which teachers and students can adapt to suit their own contexts throughout any of the units of study. It is also worth noting that the stages, while in some sense linear, are also concurrent as student researchers will frequently revisit and revise each part of the process.

Stages of the inquiry process

| 1. Engage | Stimulate students’ curiosity by providing remarkable / noteworthy facts about the issue to be analysed. What do students really want to know about the issue? (Here you could use the study design inquiry questions, an occurrence, opinions or commentary, image(s), video clips, statistics or anything that could stimulate interest or passion.) |

| 2. Formulate questions | Students should create three or four key questions that will help them understand their overarching topic. Teacher guidance is recommended here, but a political inquiry must ask questions about background to the issue, power, conflict, interests, perspectives, causes, responses and impacts. |

| 3. Research | Students gather information from teacher-provided resources and their own investigations. Teachers can provide suggestions for organising the research findings, such as note-taking templates or graphic organisers. In the research stage, students should be encouraged to work collaboratively and pool their findings. |

| 4. Analyse | Here students should use the key concepts outlined in the Characteristics of the study: causes and consequences, competing interests and perspectives, forces encouraging political stability and / or change. |

| 5. Evaluate | Using evidence, students begin to formulate answers to their specific questions, which then provides them with the ability to create statements of opinion (hypotheses or contentions) that must be able to be informed and supported by the evidence. The characteristic of ‘evaluating political significance’ is particularly relevant here. |

| 6. Communicate | Teachers may determine the format that students must adopt to communicate their findings and conclusions and assess them according to their mastery of content, the level of their inquiry skills, as well as the quality of the communication (i.e. an assessment of the product and the process). |

Different models of political inquiry are explained in Unit 2 Democracy: stability and change. A sample approach to a political inquiry is included in the section on Unit 3 and 4 Assessment. See also the Resources section for more information on guided inquiry.

Stages of political inquiry:

- Asking political questions: Questions sit at the heart of a political inquiry and are often about power, legitimacy, political stability and change, and how different political actors respond to the issues and challenges that face them and the world. When studying politics, students’ curiosity and investigations are driven by the questions they ask about contemporary issues. Students use political questions to frame their political thinking about contemporary issues and challenges. These questions should aim to be open and fertile and can be descriptive, analytical, comparative, evaluative and / or predictive. Students develop lines of argument in response to questions about contemporary political phenomena and use evidence to support their conclusions.

- Analysing and interpreting sources of information: Knowledge about politics is based on evidence that is analysed and interpreted from various political sources of information, and requires students to be able to extract information from all kinds of quantitative and qualitative data. Political sources of information can be visual, aural, graphic, numeric or textual. Sources of information can be drawn from contemporary events, relevant global actors, written accounts, polling data, perspective-based analyses, visual representations, media, news reports and documentaries and other published documents. Teachers are encouraged to use numerical data sources, such as surveys and maps (for example Pew research,Lowy Institute polls or the Lowy Pacific Aid Map) and graphs and tables (for example those created by ‘Our World in Data’). Teachers should also provide opportunities for students to consider and reflect on the inherently political, often unreliable, nature of the media nationally and globally, including forms of digital and social media. Students may locate, identify and select relevant and reliable sources of data to inform their political inquiries and to demonstrate achievement of the mandated source analysis assessment task. Alternatively, students may use sources provided to them.

Quantitative political sources may be analysed by identifying the implications of the data, considering the limitations and reliability of the data, comparing different collections of data and then using that critical thinking to arrive at supported conclusions. Qualitative political sources may be analysed by identifying the type of source, its content, author, socio-historical context, perspectives, and / or its point of view. It is important to discuss the purpose of the data and the intent of its author, but the key objective in political source analysis is the location, extraction and assessment of evidence. Sources of political information may also be used to develop an appreciation of the diverse political perspectives taken by different actors with different interests on contemporary issues. Political data of the kind mentioned above is an indispensable source of evidence for students and teachers to understand the nature of political issues today. For example, understanding climate change, development or human rights crises and / or the effectiveness of responses by global actors to these issues should be informed by the kind of factual data provided by OurWorld in Data or the Pacific Aid Map referred to above. Understanding of an election process cannot be complete without analysis of polling / voting data. Students should also be aware of the differences between reliable and unreliable information, even invalid information and the impacts of misinformation and disinformation in influencing politics. Only then can students evaluate the usefulness and reliability of sources as evidence in constructing and communicating a sound political and evidence-informed argument.

2. Applying political concepts

2. Applying political concepts

Students’ application of political concepts allows them to demonstrate their understanding of the complexity of political issues. Teachers are advised to encourage students to investigate political issues by framing questions using these key concepts. For example: Which actors have power in this issue? What kinds of power do they possess and how have they used it? What is the basis of legitimacy of this actor’s exercise of power? What is the nature of the conflict? What attempts at cooperation have occurred? Has the issue been impacted or driven by the increasing interconnectedness and interdependence of the world?

Key political concepts for this study include:

Political actor: Throughout VCE Politics, students examine a range of political actors such as states and institutions of global governance (IGGs), leaders and heads of government, political parties, non-state actors such as transnational corporations, non-governmental organisations, terrorist organisations, interest groups, and individual citizens. A political actor is simply any person, organisation or institution that becomes involved in a political issue and has some degree of power or influence. Different political actors have different interests and perspectives, different access to resources and different degrees of freedom of action.

Power: While the concept of power is contested, it is essential to an understanding of stability and change in political, economic and social systems. In this study, power is defined as the capacity of political actors to affect and influence other actors, thus it is fundamentally relational. For example, states have military power if they have significant military capacity. They may choose to exercise this military power in a number of different ways and to varying degrees, or they may choose not to use it at all. Transnational corporations have significant economic power as a result of their revenue, control of foreign assets or number of employees. As a result, they have global influence and may exercise their economic power over others to pursue their interests. Students develop an understanding of the difference between legitimate and illegitimate uses of power. Students should also be aware of the different forms of power available to political actors, including political, military, economic, technological, diplomatic and cultural forms of power. These forms of power could be used as either soft power, where compliance is voluntary and based entirely on attraction, or coercive power based on persuasion or force.

Legitimacy: Most sovereign states must legitimise their use of power over the governed in order to achieve stability. It refers to the grounds upon which governments may demand obedience from the citizens, such as winning elections, appealing to a higher authority such as a religion or providing citizens with economic prosperity and security. In this sense, legitimacy transforms power into authority. It is linked to the achievement of consensus among the population about the way they are governed, their willingness to comply for whatever reason and the maintenance of their trust. Legitimacy may also apply to other actors, such as institutions of global governance, whose legitimacy rests on their members’ acceptance of their values and processes, or non-state actors whose power may be legitimate or illegitimate.

Authority: In political science, authority is the right to exercise power. This right can stem from law, office or custom / tradition. Thus, it is based on consent and legitimacy. Authority may also be a significant source of power in itself, such as the authority deriving from the office of the Prime Minister of Australia, which gives the incumbent political, diplomatic, social and cultural power regardless of who it is.

Conflict and cooperation: Conflict, whether over resources, wealth, ideologies, world views or power is at the heart of the study of VCE Politics. Students examine a range of these conflicts, through various lenses, such as ideology (see below), theories such as realism, cosmopolitanism or liberalism, or self-interest. Political thinking about conflict requires an analysis of causes, differing interests and perspectives and consequences or outcomes. Cooperation among political actors to resolve conflicts and issues may be facilitated by national laws, institutions and processes or by the international rules-based order. This may include the work of institutions of global governance, states, non-state actors, transnational corporations, national political actors and individuals. ‘Cooperation’ requires actors to engage as national citizens rather than representatives of subnational groups and / or as global international citizens acting in the interests of the global community who demonstrate respect for the rule of law, human rights and the peaceful resolution of issues.

Political ideology: Throughout the study, students consider how the accumulated range of political ideas is articulated in ideologies which offer insights into how politics, society and the economy operate. Students may analyse constructs such as Left / Right, political spectrum, liberalism, conservatism, progressivism, authoritarianism, nationalism, capitalism, social democracy, socialism, libertarianism, populism, feminism, anarchism, communism, theism and environmentalism. The selection of an ideology to study will depend on the focus of the chosen inquiry and the nature of the case studies being used. Students consider how ideologies express ethical ideals, principles and beliefs that influence and shape political systems, political actors, policy and issues. Political ideology can be used to justify, explain, contest or change society and influence debates. It can be a lens through which contemporary issues may be viewed.

Systems and theories of government: Throughout the study, students will compare different types of governments, including democratic and authoritarian political systems, to understand the underlying principles and ideologies on which these systems are based. These may include republics, liberal and illiberal democracies, constitutional monarchies, theocracies, oligarchies and dictatorships, all of which have different ways of managing power and different understandings of the preferred relationship between government and the governed.

Governance: In the study of politics, good governance commonly means systems and processes, such as constitutions or elections, which are designed to ensure transparency, accountability, equity, participation and the rule of law. This is not only the case within democratic societies such as Australia or the United Kingdom, but also applies to the concept of the ‘rules-based international order’, also known as the liberal international order. At the very least, abiding by international law is central to this concept of global governance, which can also be understood as a set of mechanisms and institutions to manage competing and quite divergent interests between states. Additionally, democratic theories, human rights law and cosmopolitanism provide the normative foundations upon which governance institutions such as the United Nations, the International Criminal Court or NGOs, such as Amnesty International, operate.

Australian democracy and democratic principles: An understanding of democratic principles, institutions and processes is essential to students’ ability to think politically about the features and operation of Australian democracy and to analyse political issues facing contemporary Australia and the world. Democratic principles traditionally include popular sovereignty, equality, the rule of law, checks and limits on power, the protection of human rights and freedoms, majority rule and minority rights. Democratic institutions and processes should express and embody democratic principles. Such institutions include constitutional government, representative government, responsible parliamentary government, free and fair elections, a free and diverse media; mechanisms for ensuring accountability of the elected representatives; transparency and integrity of political decision-making, term limits for parliaments and office holders and avenues for all citizens to participate in democratic processes and civic life.

Interests: The ‘interests’ of political actors refers to what those actors perceive to be desirable in any situation or at any time. Interests can change depending on circumstances. They are often material and self-serving rather than altruistic or other-directed, as ‘aims’ tend to be. Aims are the established and published goals of political actors, such as the objectives of many transnational corporations to uphold the UN Sustainable Development Goals, which may actually conflict with their interests in certain circumstances.

National interest: Governments use this term to justify their policies and actions when those policies and actions are the subject of debate. The national interest motivates both domestic and foreign policy and is central to realist approaches to policy, as it prioritises the state and its citizens over other states and the global community. There are certain national interests that are common to all states: security, prosperity, stable international and regional relationships, and the achievement of international or regional standing. How these interests are defined by the state depends on the circumstances and the perspectives of the political actors involved.

Nation: This is an important concept in the study of politics as it is bound up with questions of identity and conflicts over sovereignty and territory. A nation refers to the collective identity of a group of people based on a common culture, history, language, ethnicity and homeland. By definition, they do not have recognised sovereignty over defined territory; if they did, they would be referred to as a ‘nation-state’.

Sovereignty: There are a number of different types of sovereignty depending on the context. In the global arena it refers to the basis on which states claim the right to govern over their territory and their citizens, without interference from other political actors and to represent their territory and citizens in the global arena. The Charter of the United Nations upholds the sovereign equality of its member states (Article 2) so it is tied to the concept of statehood. In the domestic political sphere, it may refer to a sovereign – a monarch with supreme power – or the sovereign power of a parliament in the Westminster system or popular sovereignty in liberal democratic theory. Sovereignty is often contested both within societies and by those outside them.

State: There are various ways of theorising the state in political science. What is common to all of them is that a state has recognised and sovereign control over a defined territory, where this control entails the ability to regulate many aspects of citizens’ lives through public institutions, ensure compliance with the state’s laws, maintain order, monopolise the legal use of coercion, impose public funding through taxation and represent the citizens on the international stage.

Global interconnectedness: This refers to the increasing links and exchanges between political actors and their resulting interdependence. This is due to the process of global economic and social integration (formerly referred to as globalisation) and the establishment of institutions of global governance, which began in earnest after the Second World War and which continues to impact on human affairs in a myriad of ways (socially, economically, environmentally, politically, culturally and technologically). It is concerned with the increasing frequency, speed, range and intensity of cross-border flows – exchanges of people, knowledge and ideas, goods, services, financial transactions, military and cyber transactions and social and cultural values. It incorporates the role of the globalised media in national, regional and global politics, both as an essential transmitter of political information, and as a key political actor. Transnational corporations also continue to play a significant political role in the interconnectedness and interdependence of the world. Global interconnectedness is essential to an understanding of contemporary political issues in terms of its impact on stability and change, political significance, differing interests and perspectives and questions of power. Additionally, this interconnectedness and interdependence has also led to a simultaneous fragmentation of identities, values and beliefs along with increasing inequalities and potential for conflict.

3. Analysing causes and consequences

3. Analysing causes and consequences

The approach to identifying and analysing causes of an issue or conflict should be guided by the type of issue under examination. In the case of a global issue such as climate change, for example, there are clearly identifiable physical causes, such as global warming, which students must know. Drilling down further, they may also identify the interdependence of the world in terms of communications technology, trade, consumerism and the activities of transnational corporations as further contributors to such an issue. Students may also want to consider the continuing causes or drivers, of issues, such as the national interests of states, great power rivalry or ethnic, ideological and religious divisions. In terms of domestic issues, these global interconnections may still be important, as well as the interests and perspectives of domestic political actors, such as political parties, mixed public opinion and lobbying. Finally, as part of understanding the scope of the issue, a brief examination of the historical background to the issue is also desirable, as long as students do not proffer historical causes only. They must always be able to explain how an historical cause continues to drive the issue in the present. Causes precede the issue and consequences succeed the issue. In between, the actions of political actors produce further consequences, which can either exacerbate or alleviate the issue. Students must be able to explain and analyse the dynamic relationship between causes and consequences as a way of understanding conflict and cooperation, and of evaluating political significance.

4. Identifying and analysing differing political interests

4. Identifying and analysing differing political interests

Political interests motivate political action. As they may be concealed and changeable, as well as being publicly stated, it may be difficult for students to identify these interests with complete certainty. Students and teachers should be guided in this case by a range of expert commentary, which can then form the basis for identification and analysis of political interests. This also provides a number of opportunities for students to assess the reliability of source material, comparing fact with opinion as far as possible. Students should also examine opposing interests in the issue as a further way of assessing the significance of the political actions taken and the reliability and validity of the stated interests. For example, the Australian government may identify its national interests as maintaining regional stability, which may act as a motivation for strengthening the American alliance or forming closer economic relationships with countries in the Indo-Pacific region. But these stated interests may mask other perceived interests, such as containing the rise of China. Students should be encouraged to see and discuss political interests as fluid, often unreliable and dependent on circumstance.

5. Identifying and analysing differing political perspectives

5. Identifying and analysing differing political perspectives

In contrast to political interests, political actors’ perspectives are more easily identified as they are a public representation of their values, norms or world views. In the case of many non-state actors, regional organisations or institutions of global governance, the perspectives are outlined in a set of unifying aims, a vision, a charter or other founding document. The perspectives underlying state action, on the other hand, are closely tied to the leadership of the state and the type of political system involved and may be expressed in white papers, legislation or other policy documents. Perspectives can be highly contested within political systems and are often the cause of conflict or dissension. It is vital that students identify and analyse the different perspectives of political actors involved in an issue, the significance of the relationship between them and the implications of those perspectives in order to understand the political dynamics of that issue and to determine the logic and reasonableness of information provided.

6. Discussing political stability and change

6. Discussing political stability and change

It is through discussion that students learn to appreciate the wide range of perspectives on various issues and to listen respectfully to opposing views. Students of politics and political actors themselves benefit from such discussion in order to effect change or maintain things as they are. Political stability can refer to a number of things: widespread acceptance of the values, institutions and processes which underpin a functioning society; a lack of change over time in responses to political issues or arrangements or the ability to ‘bounce back’ or revert to the status quo in the face of upheaval or disturbance. Political change refers to any alteration or modification in political institutions, processes or values and it usually occurs when there is an unforeseen event or a significant amount of disagreement with prevailing norms – what might be referred to as ‘black swans and grey rhinos’. A key skill for students of politics is to disentangle the forces that are maintaining stability and those striving to disrupt the status quo and so achieve change. Or in the case of an unforeseen event (the black swan), students must be able to identify the causes and the consequences of the event to assess the subsequent degree of stability or change. A discussion of political stability or change in a political issue also requires students to identify the arguments and evidence used to persuade others to change or remain the same.

7. Evaluating political significance

7. Evaluating political significance

This characteristic of thinking politically sits at the apex of students’ skills acquisition. It requires students to think through the possible criteria for assessing significance and then come to a judgement and provide supporting arguments. There are a number of ways in which an event, issue or actor could be judged to be politically significant or important. To establish relevant criteria, students should ask questions about the event, issue or actor, such as:

- Who has power in this situation? Who does not?

- What is the scale of the issue itself – geographically and temporally? How many people are affected?

- Which political actors are involved and are they working towards change or stability?

- How common or uncommon is the event, action or issue? What are the immediate and ongoing consequences?

- How important is the event or issue to various groups or political actors and for what reasons?

- What are the reasons that the event, issue or actor may not be considered significant?

Once the student has identified the causes and consequences, interests and perspectives and supporting evidence on both sides, they should be able to mount an argument that something is or is not politically significant.

Students need to investigate the actors concerned, their power and where their power comes from, whether the use of power is legitimate in Australia, what their interests and perspectives are in the issue, what justifications or rationalisations they put forward and what the immediate and longer term consequences are or might be. Are they working for political change or to maintain the status quo? Answers to these questions will enable students to make a judgement about the political significance of the issue and the actions taken.

8. Constructing reasoned and evidence-informed arguments

8. Constructing reasoned and evidence-informed arguments

As the study of politics is all about power, conflict, political interests and perspectives, the achievement of stability and change and political significance, it is evident that there is nothing hard and fast or right and wrong in terms of opinions or judgements. What is necessary is for the student to be able to identify the strengths and weaknesses of various political perspectives and actions and be able to assign a weighting to these positions through evidence, reasoning and a consideration of underlying values. For example, a student may decide that methods used by political actors to achieve their interests are indefensible, but only on the basis of democratic principles or the value of human rights, whereas there may be other justifications for these methods. Students’ own arguments or contentions must also be supported by factual evidence or persuasive ‘expert’ opinions. Their analyses and evaluations should demonstrate an understanding of the relative weight of the evidence used and the strength of any opposing arguments.

Developing a program

The VCE Politics Study Design outlines the nature and sequence of learning and teaching necessary for students to demonstrate achievement of the outcomes for a unit. The areas of study describe the specific knowledge and skills required to demonstrate a specific outcome. Teachers are required to develop a program for their students that meets the requirements of the study design including areas of study, outcome statements, key knowledge and key skills.

Teachers are advised to plan the delivery of a program of study based on the recommended 50 hours of class time per unit. Teachers should be careful to closely align their learning activities to the key knowledge and key skills. For each unit, teachers should select contemporary examples and case studies and design assessment tasks that will facilitate students’ acquisition of key knowledge and skills.

The inquiry questions

The inquiry questions

Each area of study includes key inquiry questions that precede the description of the area of study. These questions can be used in ways that promote political understanding and support student learning. For example, the questions can be embedded in lessons throughout Units 1 to 4 as learning intentions and they may also be used to structure political inquiry, employed as guiding questions in the inquiry options in Unit 2 or used to shape assessment tasks. (See the section on Political inquiry in the Characteristics of the study.)

Approach to the options

Approach to the options

The options represent flexible opportunities for student inquiry into the big political issues of the times, both within Australia and internationally. Every option is capable of being used to teachkKey knowledge and skills. In Units 1 and 2, teachers can choose to teach one or a number of options for the whole class or they may decide to allow students to choose those options that most interest them. In Units 3 and 4, the demands on teachers’ and students’ time will mean that in most cases, options will be selected to maximise opportunities to overlap knowledge and skills wherever possible.

Selecting options and creating pathways

Selecting options and creating pathways

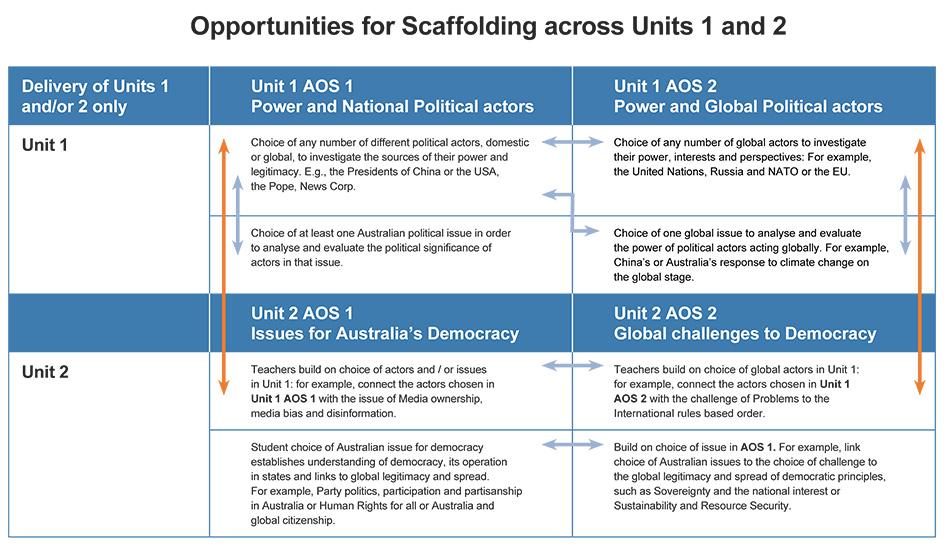

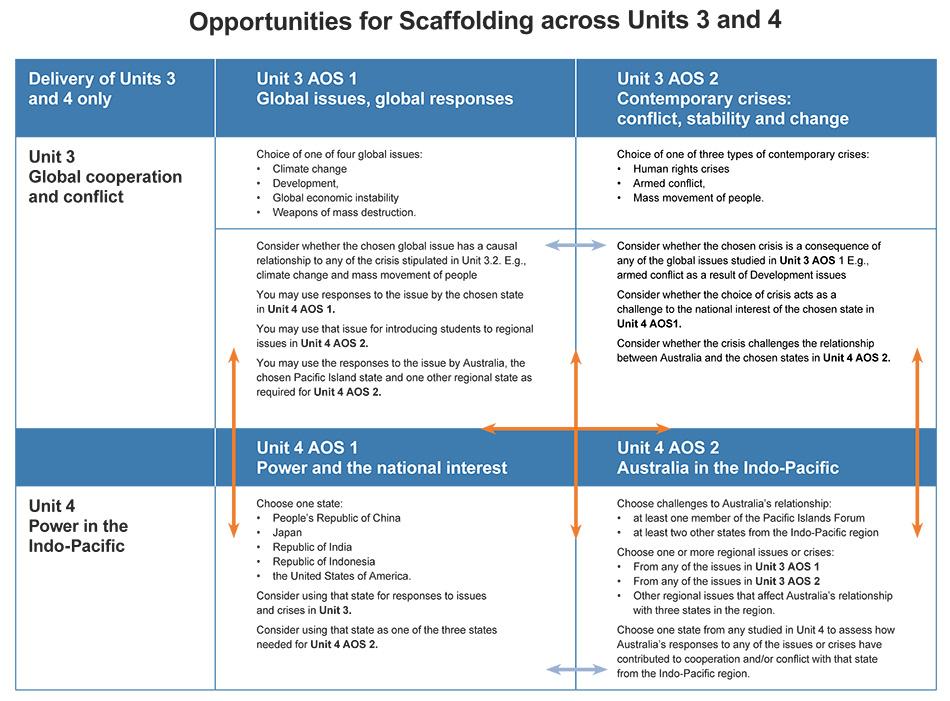

VCE Politics provides considerable scope for accommodating student interest and teacher expertise, as well as building on students’ knowledge and skills across the four units of study. The four units are comprised of eight areas of study, all of which contain options that teachers can use as contexts for the development of key knowledge and skills through political inquiry. The selection of these options can provide a cohesive framework of learning across all four units or across two only – Units 1 and 2 or Units 3 and 4. When selecting options, teachers should aim to develop a clear pathway to allow students to build on prior knowledge. Any examples and case studies used must be from within the last 10 years, although a brief overview of historical causes of issues or crises can be helpful as an aid to student understanding.

The table below indicates possible synergies and connections between options that could provide learning pathways across the units.

Figure 2: Possible connecting pathways between the units For schools who offer only Units 1 and 2 or who offer only Units 3 and 4, please note only the parts of the table that are relevant to you. For a more detailed map of the VCE Politics Study Design, which highlights the questions to consider when developing a course, see the attached document Developing a course table and the descriptive information in the sections on each unit.

Selection of case studies and examples

Selection of case studies and examples

The most important determinants of the selection of case examples are their contemporary nature (within the last 10 years), their ability to meet the key knowledge and skills, and their usefulness across the course as a whole. Teacher and student interest and expertise should also be considered. Although teachers may choose to present as few case studies as possible due to the pressures of time, students need to be able to gain an accurate understanding of the complex nature of political issues, which means that many different examples will be beneficial. These examples and case studies can be built up over the course of the year or the course of two years, so that students’ knowledge of different political actors and their interests, Australian politics and issues, and regional and global issues is deepened.

Applying the Characteristics of the study in teaching and learning

Applying the Characteristics of the study in teaching and learning

The Characteristics form a natural framework for the investigation into the various options / choices provided across Units 1–4. Within every case study, students can be introduced to the meaning of the characteristics and their corresponding skill.

For example, in Unit 3 Area of Study 1, teachers may choose to investigate the issue of Development. The Unit 3 Area of Study 1 Outcome dictates that ‘analysing causes and consequences’ is the characteristic that should be taught and the key skills point to the way that can be done:

- ask and analyse a range of political questions to investigate one global issue (in this case, development), such as ‘what does the term mean? How can it be measured? Is one indicator of development any better than another? What global actors have something to say on this issue?’

- analyse and interpret a range of sources of information on one global issue, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, the Human Development Index and the Multidimensional Poverty Index, the World Bank reports, Our World in Data, the investigations and work of NGOs such as Oxfam or Save the Children and many others.

- assess the impact of global interconnectedness on one global issue, through considering whether our globally interdependent world has improved or exacerbated issues of development and inequality. Students could link their investigation of the impacts of global interconnectedness on any chosen issue or contemporary crisis (development, global economic instability, climate change, weapons of mass destruction, armed conflict, mass movement of people and human rights challenges) with the states they will study in Unit 4.

- analyse the causes and consequences of one global issue – for example, what are the driving factors behind poverty, inequality and a lack of development? Why does it matter? How many people are affected across the world? Students could also see World Vision, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) or the Executive summary of this IMF report on the causes and consequences of income inequality.

- analyse how the interests of different global actors may contribute to the causes and consequences of one global issue. What is the significance of national interests, political systems and ideologies, the interests of transnational corporations or non-state actors in contributing to the causes of development issues and the continuing impacts of those problems?

- analyse the different perspectives of global political actors on one global issue and the reasons for those different perspectives. How do various governments from different parts of the world (for example, the Pacific Island countries or emerging economies of the Indo-Pacific region) see the issue of development and its resolution? What are the perspectives of other global actors on this issue?

- discuss how responses by global actors and challenges to resolution have contributed to political stability and / or change. Students can examine trends and collectively arrive at an understanding of the chief challenges to resolution of this issue.

- evaluate the political significance of the issue of development. By this time students should have collected plenty of evidence to make a judgement about the significance of the issue, bearing in mind the definition of political significance outlined in the Characteristics (see ‘Evaluating political significance’ on page 13 of the study design) and discussed in the section on Characteristics of the study in this document. The relevant part of the definition is ‘To reach a judgement, students analyse political stability and change and cause and consequence, analyse competing interests and differing perspectives, evaluate the effectiveness of responses and their impacts and outcomes, and assess the degree to which the interests of political actors involved in an issue were achieved.’

- construct an argument to evaluate the ability of global actors to respond effectively to one issue, using evidence from sources. Again, students should have been collecting evidence and marshalling their arguments so that they can justify an opinion on the likely resolution of the issue.

Figure 1: Relationship between achievement of the outcomes for each area of study and the key knowledge, key skills, case examples and assessment

Unit 1: Politics, power and political actors

This unit focuses on introducing students to the essential concepts and characteristics of the study of VCE Politics. Teachers are advised to plan this unit carefully in order to ensure a smooth progression of knowledge and skills into Unit 2. The difference between political actors in the domestic sphere and political actors who are able to act globally should not be over-emphasised as many of these actors can act within both arenas depending on the context and the nature of their power and legitimacy.

The political issue(s) selected for investigation in both areas of study should not be too large or complex. Teachers should choose issues that involve some kind of conflict, featuring different political actors with their different political interests and perspectives and making clear where their source of power is apparent. There is a list of possible political issues for Area of Study 1 on page 18 of the Study Design. Suitable political issues for students to examine in Area of Study 2 include climate change, conflicting perspectives and interests over the Great Barrier Reef or the Amazon rainforest, an emergency human rights situation such as refugees, or the activities of a Transnational Corporation in a particular state (such as the pharmaceutical industry’s approach to intellectual property rights in developing countries or the activities of agricultural / mining companies in Brazil) or an international incident such as a protest in Iran. A series of short and varied case studies of political issues can introduce students to a range of actors, a range of powers, a range of systems and ideologies and a good understanding of the intersection between domestic and global actors. It also provides a solid platform for the remaining units of study.

Unit 2: Democracy: stability and change

In contrast to Unit 1, this unit is designed to introduce students to an in-depth political inquiry with a focus on democratic principles and values. Inquiries are particularly suitable for the study of politics as most if not all political inquiries are based on open-ended questions and can be framed to provide contexts for developing conceptual understanding. Teachers can determine the model of inquiry and the extent of teacher guidance. The table below offers four models but any combination of inquiry types is possible.

| Type of inquiry | Provision of framing question(s) | Research method and provision of case material | Construction of supported contention in response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis requiring confirmation e.g. the current global and social media networks enhance Australian democracy | Teacher | Teacher | Student |

| Structured inquiry | Teacher provides over-arching question and sub-questions | Teacher provides the procedure and some case material Students may add to case material | Student |

| Guided inquiry | Teacher provides the over-arching question; students formulate more specific research questions | Students work in groups under teacher guidance to decide procedure and suitable case material | Student |

| Open inquiry | Students determine both over-arching and sub-questions | Students singly or in groups design procedure and locate case material | Student |

Teachers should ensure that democratic principles, institutions and processes as laid out in the key knowledge and key skills on pages 22 to 25 of the VCE Politics Study Design are clearly understood by students before attempting the inquiries. Lessons will need to be carefully planned in order to provide adequate time for both ‘pre-teaching’ and the inquiries themselves.

Assessment of student achievement in a political inquiry can incorporate a number of assessment tasks, such as an analysis and / or evaluation of sources, extended responses or short-answer questions, a multimedia presentation, an essay or a political debate. See sample approaches to assessment.

Unit 3: Global cooperation and conflict

In this unit, the focus is on understanding the dynamics of conflict and cooperation through an investigation into one global issue and one contemporary crisis. The difference is that the global issue must be one of the ones stipulated on page 27 of the VCE Politics Study Design and be comprehensively investigated using the key knowledge and key skills. The contemporary crisis, on the other hand, may be a more localised conflict that is representative of one of the three stipulated crisis areas: human rights, armed conflict or the mass movement of people. Examples of more localised crises are a flareup of tensions across borders; discrimination or genocidal practices against particular groups on the basis of race, ethnicity or gender; authoritarian responses to protest movements; inter- or intra-state conflicts; large-scale movements of people across borders (anything that involves large numbers of people, more than one state and leads to the intervention of institutions of global governance, regional groupings and other state and non-state actors). Refer to the key knowledge on page 28 of the study design, which outlines the parameters of the responses by actors to the crisis. Students should learn to analyse and evaluate the political significance of these issues and crises and understand the factors leading to stability and / or change, including global interconnectedness and interdependence.

Teachers should also be mindful of the change to the rules regarding causation of the issue and crisis chosen. While it is useful in some cases for students to be aware of longer term or historical causes, these types of causes will not be acceptable as the focus of an answer to any question on causes, whether this be in school-based or external assessment. Causes must be short-term only.

Finally, as indicated in the above section on Selecting options and creating pathways, teachers should plan their choice of issue and crisis in such a way as to maximise their usefulness across Units 3 and 4. The choice of global issue, its causes, the impact of global interconnectedness, responses by actors (including international laws and challenges to resolving the issue) can all be used across the two areas of study in Unit 4. It is the same with the choice of contemporary crisis.

Unit 4: Power in the Indo-Pacific

The final unit of study gives students the opportunity to study one state from the Indo-Pacific in depth, Australia’s relationships with three states in the region, as well as Australia’s responses to issues that affect those states. It should be noted that there are points of overlap and intersection between the two areas of study in this unit, which teachers may want to incorporate into their course and lesson planning.

Possible intersections between 4.1 and 4.2 in selected key knowledge and key skills

| Unit 4, Area of Study 1: Power and the national interest | Unit 4, Area of Study 2: Australia in the Indo-Pacific | |

|---|---|---|

| Selected key knowledge |

|

|

| Selected key skills |

|

|

Resources

Unit 1 Area of Study 1

- VCE Politics Unit 1 and 2 Explanations

- Museum of Australian Democracy website

- Parliament of Australia website

- Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) voting information

- AEC Get Voting

- AEC data

- Politics – ABC News

- ABC’s BTN and BTN High (to find issues)

Unit 1 Area of Study 2

- UN: Our work – Uphold International Law

- UN Treaty Collection

- Step-by-Step Outline for Organizing a Model UN session

- Lowy Institute Asia Power IndexSoft Power 30 (formerly Soft Power Index)

- Freedom House

- Worldwide Governance Indicators (World Bank)

- OECD Statistics

- Our World in Data

- World Press Freedom Index

- Principled Aid Index

- Human Development Index (HDI)

- Pew Research Global Indicators Database

Unit 2 Area of Study 1

- See Options

Unit 2 Area of Study 2

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Global Democracy

- Our World in Data – Democracy

- Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance – Global State of Democracy indices

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Crisis and fragility of democracy in the world

- See Options

Unit 3 Area of Study 1

- Climate Change

-

- Climate Action Tracker

- Climate Science: What you need to know (video)

- Our World in Data: Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- Climate Council: What does net zero emissions mean?

- The Conversation: The five corrupt pillars of climate change denial

- NASA: Responding to Climate Change

- UN Environment Programme

- UN Climate Change and the UNFCCC

- ABC News: Climate Change

- Global economic instability

- Development

- Weapons of mass destruction

Unit 3 Area of Study 2

- Human rights crises

- Armed conflict

- Mass movement of people

Unit 4 Area of Study 1

- Reports about each state:

- Lowy Institute Asia Power Index

- Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map

- DFAT’s explanations of regional architecture (such as the Quad and ASEAN)

- BBC News: China

- BBC News: Japan

- BBC News: India

- BBC News: Indonesia

- BBC News: USA

Unit 4 Area of Study 2

- DFAT

- Lowy Institute Asia Power Index

- Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map

- ANU 'Australia comes of age as Indo-Pacific power’

- DFAT Australian Cultural Diplomacy Grants Program

- Soft power 30: Australia

- Progressive and conservative think-tanks

- The Guardian (Foreign Policy)

- The Australian

- Notable commentators such as Hugh White, Peter Jennings, Greg Sheridan, Kevin Rudd, Paul Keating

- Political party websites (for opposition and minor party policies)

- Communications from regional groupings (e.g. ASEAN or Pacific Island Forum)

- News sources of opinion on Indo-Pacific nations (e.g. Global Times in China)

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Perspectives in the VCE

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Perspectives in the VCE

On-demand video recordings, presented with the Victorian Aboriginal Education Association Inc. (VAEAI) and the Department of Education (DE) Koorie Outcomes Division, for VCE teachers and leaders as part of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Perspectives in the VCE webinar program held in 2023.

Employability Skills

The VCE Politics study provides students with the opportunity to engage in a range of learning activities. In addition to demonstrating their understanding and mastery of the content and skills specific to the study, students may also develop employability skills through their learning activities.

The nationally agreed employability skills* are: Communication; Planning and organising; Teamwork; Problem solving; Self-management; Initiative and enterprise; Technology; and Learning.

| Assessment task | Employability skills selected facets |

|---|---|

| A political inquiry | Communication (sharing information, reading independently, writing to the needs of the audience, persuading effectively) Problem solving (developing practical solutions, testing assumptions taking the context of data and circumstances into account) Planning and organising (planning the use of resources including time management; collecting, analysing and organising information) Initiative and enterprise (generating a range of options, being creative) Self-management (evaluating and monitoring own performance, taking responsibility) Learning (managing own learning, having enthusiasm for ongoing learning) Technology (using IT to organise data) |

| Analysis and evaluation of sources | Communication (sharing information, writing to the needs of the audience, persuading effectively) Problem solving (testing assumptions taking the context of data and circumstances into account) Planning and organising (collecting, analysing and organising information) Self management (evaluating and monitoring own performance, articulating own ideas and visions) Learning (managing own learning, having enthusiasm for ongoing learning) |

| Extended responses | Communication (reading independently, writing to the needs of the audience; persuading effectively) Problem solving (testing assumptions taking the context of data and circumstances into account) Planning and organising (collecting, analysing and organising information) |

| Short-answer questions | Communication (writing to the needs of the audience, persuading effectively) Planning and organising (collecting, analysing and organising information) Learning (managing own learning) |

| An essay | Communication (sharing information, writing to the needs of the audience, persuading effectively) Problem solving (testing assumptions taking the context of data and circumstances into account) Planning and organising (collecting, analysing and organising information) Self management (evaluating and monitoring own performance, articulating own ideas and visions) Learning (managing own learning, having enthusiasm for ongoing learning) |

*The employability skills are derived from the Employability Skills Framework (Employability Skills for the Future, 2002), developed by the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Business Council of Australia, and published by the (former) Commonwealth Department of Education, Science and Training.

Implementation videos

VCE Politics (2024) implementation videos

Online video presentations which provide teachers with information about the VCE Politics Study Design for implementation from 2024.

VCE Politics guidelines

(May 2025)

A set of Guidelines for the VCE Politics Study Design Units 1-4 from 2024.